Essay in the New Haven Review: The Art of the Literary Fake (with violin)

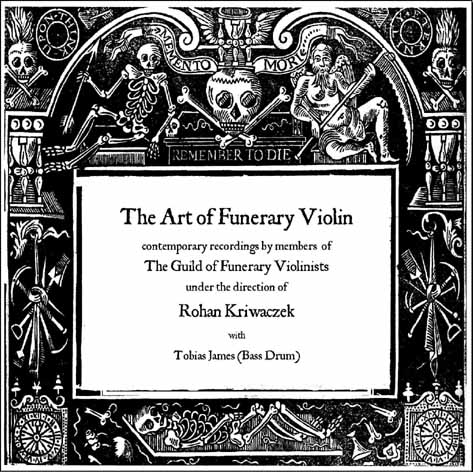

The New Haven Review's issue #10 (summer) is now out, and it includes my 9,000-word essay "The Art of the Literary Fake (with violin)," which is an exploration of literary fakes. It focuses on a book entitled An Incomplete History of the Art of Funerary Violin but also explores strange facts, an odd book of crayfish names, an eccentric penguin researcher tome, and much more. Here's the opening of the essay, which is the longest piece of nonfiction I've written since my essay on Angela Carter back about 20 years ago. Other contributors to this issue include Nick Mamatas. You can order the journal here. Thanks to Brian Slattery for commissioning the piece.***This sentence is a fake.This sentence is the original.This sentence is an animal, not a series of words. Michal Ajvaz's short story "Quintus Erectus" provides an instructional metaphor with regard to literary fakes, a form with which readers and reviewers have a long yet uneasy history. "Quintus Erectus" describes a capybara-like South American mammal that, when it stands on its hindquarters, "presses its hands closely to the body, turns its head to the attacker and remains motionless...two vertical strips of dark hair...evoke an impression of human hands with fingers," while coloration on the head "depicts the human face." At a distance of three meters "we can easily mistake the animal for a man; from a distance of five meters the animal is indistinguishable from a man." In the story, this unsettling illusion creates a feeling of wrongness and nausea in many observers. Are they seeing an animal or a human being? Is the text itself really a story or is it a disturbing something other, pretending to be a story?The story of Quintus Erectus in some ways mimics the reaction in certain quarters to the literary fake---a piece of fiction that pretends in some way to be true. Is it fact or fiction? Is it good fun or something more disturbing? By operating under the auspices of traditionally nonfictional modes to tell its story, the literary fake chooses to bring the reader to suspension of disbelief through means that include extreme guile---and, in cases where the reader recognizes the trick, continues to amuse, entertain, and say something interesting about the human condition regardless. As such, it destabilizes our view of reality, which can be uncomfortable, sometimes unforgiveable, especially if we think someone is laughing at us. We don't always appreciate things that look like other things, even if there's a purpose to the mimicry; perhaps this is a vestige of an ancient evolutionary trait that allowed us to discern between the harmless and the harmful.Nor do some readers, apparently, like to think they are being made to believe something false against their will. Fakes are especially divisive at two essential moments in time: when they successfully slip past the reader’s defenses and when the reader discovers the deception. Whether this latter point occurs soon after picking up the book or halfway through it, a literary fake eventually forces the reader to decide whether to be sympathetic or hostile toward the fakery.Fakes may also be viewed with suspicion as artificial constructs, identified as stories in which the skeleton appears to exist on the outside of the body. Fiction is meant to be an uninterrupted dream or movie for the reader, we are often told, and those struts and supporting walls should always be inside the house of the narrative; only in nonfiction do we expect to see the architecture.The irony of this view of fakes as an unnatural form is that most examples are forged by that most liberated state of mind: ecstatic imaginative play, poured into the constraint and thus given shape and structure. However, and here irony piles up upon irony, imaginative play (and, in some cases, results that exist purely as an offering on the altar of Play) creates another issue. Play isn't academically rigorous, can't be easily quantified, and suggests a border that criticism cannot cross. The Quintus Erectus that lies peacefully in the morgue, awaiting dissection, suddenly slips through our fingers when we produce the scalpel, and then reappears, grinning at us mysteriously from a chair across the room. It's as if a mischievous but highly intelligent ghost haunts the text. To speak of a ghost directly, and especially an unpredictable ghost, is to be seen as childish or superstitious, even though we are all childish and superstitious.

The New Haven Review's issue #10 (summer) is now out, and it includes my 9,000-word essay "The Art of the Literary Fake (with violin)," which is an exploration of literary fakes. It focuses on a book entitled An Incomplete History of the Art of Funerary Violin but also explores strange facts, an odd book of crayfish names, an eccentric penguin researcher tome, and much more. Here's the opening of the essay, which is the longest piece of nonfiction I've written since my essay on Angela Carter back about 20 years ago. Other contributors to this issue include Nick Mamatas. You can order the journal here. Thanks to Brian Slattery for commissioning the piece.***This sentence is a fake.This sentence is the original.This sentence is an animal, not a series of words. Michal Ajvaz's short story "Quintus Erectus" provides an instructional metaphor with regard to literary fakes, a form with which readers and reviewers have a long yet uneasy history. "Quintus Erectus" describes a capybara-like South American mammal that, when it stands on its hindquarters, "presses its hands closely to the body, turns its head to the attacker and remains motionless...two vertical strips of dark hair...evoke an impression of human hands with fingers," while coloration on the head "depicts the human face." At a distance of three meters "we can easily mistake the animal for a man; from a distance of five meters the animal is indistinguishable from a man." In the story, this unsettling illusion creates a feeling of wrongness and nausea in many observers. Are they seeing an animal or a human being? Is the text itself really a story or is it a disturbing something other, pretending to be a story?The story of Quintus Erectus in some ways mimics the reaction in certain quarters to the literary fake---a piece of fiction that pretends in some way to be true. Is it fact or fiction? Is it good fun or something more disturbing? By operating under the auspices of traditionally nonfictional modes to tell its story, the literary fake chooses to bring the reader to suspension of disbelief through means that include extreme guile---and, in cases where the reader recognizes the trick, continues to amuse, entertain, and say something interesting about the human condition regardless. As such, it destabilizes our view of reality, which can be uncomfortable, sometimes unforgiveable, especially if we think someone is laughing at us. We don't always appreciate things that look like other things, even if there's a purpose to the mimicry; perhaps this is a vestige of an ancient evolutionary trait that allowed us to discern between the harmless and the harmful.Nor do some readers, apparently, like to think they are being made to believe something false against their will. Fakes are especially divisive at two essential moments in time: when they successfully slip past the reader’s defenses and when the reader discovers the deception. Whether this latter point occurs soon after picking up the book or halfway through it, a literary fake eventually forces the reader to decide whether to be sympathetic or hostile toward the fakery.Fakes may also be viewed with suspicion as artificial constructs, identified as stories in which the skeleton appears to exist on the outside of the body. Fiction is meant to be an uninterrupted dream or movie for the reader, we are often told, and those struts and supporting walls should always be inside the house of the narrative; only in nonfiction do we expect to see the architecture.The irony of this view of fakes as an unnatural form is that most examples are forged by that most liberated state of mind: ecstatic imaginative play, poured into the constraint and thus given shape and structure. However, and here irony piles up upon irony, imaginative play (and, in some cases, results that exist purely as an offering on the altar of Play) creates another issue. Play isn't academically rigorous, can't be easily quantified, and suggests a border that criticism cannot cross. The Quintus Erectus that lies peacefully in the morgue, awaiting dissection, suddenly slips through our fingers when we produce the scalpel, and then reappears, grinning at us mysteriously from a chair across the room. It's as if a mischievous but highly intelligent ghost haunts the text. To speak of a ghost directly, and especially an unpredictable ghost, is to be seen as childish or superstitious, even though we are all childish and superstitious.