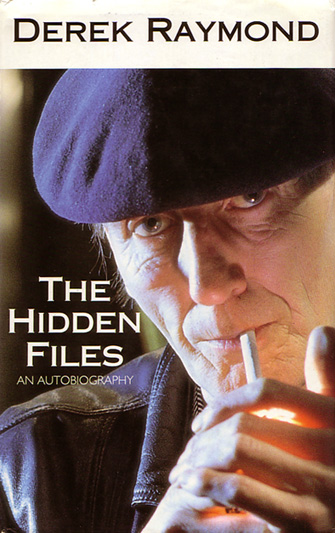

Derek Raymond's The Hidden Files, An Introduction

(Taken from this interesting webpage about Raymond, with many book covers.)Having read or re-read all of Derek Raymond's novels, save one, I am turning my attention to his autobiography, The Hidden Files--a somewhat difficult out-of-print book to get a copy of, and not particularly cheap, either.The descriptions on the dust jacket of The Hidden Files includes this insight, rather more sensationalistic than his actual fiction:

(Taken from this interesting webpage about Raymond, with many book covers.)Having read or re-read all of Derek Raymond's novels, save one, I am turning my attention to his autobiography, The Hidden Files--a somewhat difficult out-of-print book to get a copy of, and not particularly cheap, either.The descriptions on the dust jacket of The Hidden Files includes this insight, rather more sensationalistic than his actual fiction:

A memoir on [Raymond's] writing techques and inspiration, peppered with autobiographical vignettes, it provides a unique insight into the dark recesses of a writer's mind. And in charting his own erratic career, Raymond reveals impeccable credentials as a chronicler of the high-life and low-life sleaze. Born into a wealthy, eccentric, upper-middle class family and educated at Eton, he soon dropped out--a traitor to his class--and immersed himself in London's criminal underworld of the 1960s. His acquaintance with crime has served him well as a novelist; his bleak, violent accounts of psychopaths, his cynical, cold-blooded detective, his musings about tormented, cold-blooded killers and meditations on the nature of evil paint chillingly real portraits of the demons at the heart of society.

Although I've only just started in on The Hidden Files, I thought I'd give you a taste of it by typing up the introduction, which you can find below the cut. In it, Raymond talks about the origins of the title--the fact there are parts of ourselves we keep hidden from other people, and suggesting that in part this is because those hidden files feed into the fiction. His description of the immersive aspect of writing fiction rings very true to me--and is making me increasingly wary of an unthinking embrace of social media and the resulting fragmentation of our attention spans, the wholesale creation of not just open channels but open thoroughfares through which other people's personalities, ideas, and ephemera smash into our consciousnesses. Is there damage to the hidden files as a result? Even, perhaps, corruption that we don't notice? Is it connectivity or assault? Anyway, this is a tangent to Raymond's point, I'm sure, but something that struck me.I'll report back on The Hidden Files when I finish it. In the meantime, here're the links to my prior Derek Raymond post and, of course, Raymond's introduction, British spellings preserved.Derek Raymond's Factory NovelsThe Pathology of Derek Raymond's Dead Man Upright***Introduction, The Hidden Files by Derek RaymondI have said a lot about writing in these memoirs, with particular reference to the black novel. I could not have described my life in any depth without almost constant reference to the work that has given it meaning—the effect that being a writer has had, not only on myself as a person, but on how I have transferred my experience to others—in fact, how I regard the other. Yet, in order to be able to take a realistic view of the other, to feel him, know him and in an apparently magical way to some extent become him, it is necessary to do that difficult thing, become oneself first.Writing has been my life. Ever since I was a teenager, even if I couldn’t get hold of pencil and paper, I have continually thought about writing; even when I was blocked by lack of ideas or energy, or prevented from writing by circumstances, I still started automatically trying to work out how I would transform into writing whatever I might be doing.For, as well as the conclusions I have drawn from everything important that has happened to me, every emotion or passion that has ever taken control of me—love, anger, fear, desire—I have, somehow or other, sooner or later, converted it into writing. Writing is what I understand by living.In writing this book I have found that it isn’t what you remember that matters so much as why and above all how you remember it. Some of my experiences, even though they made headlines, had no more than a superficial impact on me once I had drained them of whatever they had to teach me, the rest being worth no more than a story told in a bar. Yet other experiences, apparently insignificant, left indelible traces on me.The criteria I have used as a selection method are twofold. First, does the presence in this book of a given experience really seem necessary? Second, is what I am including likely to distress or embarrass anybody who figured in it?I apologise for my style. I have never tackled writing memoirs before; I find it is not in the least like writing a novel, which virtually imposes its own structure once it gets going. A novel has a beginning, a middle, and an end, whereas a life still in progress most definitely hasn’t. Secondly, my style bears the marks of a lot of thinking—as often as not, my own homespun thinking about the thinking of others, notably in the fields of psychology and metaphysics, the meaning of which in relation to the black novel I have had to try and work out for myself, and which I have tried to apply to some of the subjects treated here. Removed from the sphere of the novel, in which they are implied, not stated, some of the ideas I have tried to capture are too subtle and delicate to explain without images.***I think I had also better say something else about my personality.There is a part of me which, according to a lot of people—who know me extremely well and who therefore can’t all be wrong—is reserved or cold; a part the other person, no matter how close to me, can never really reach.I am afraid this not very flattering judgement is correct. A part of me is made up of a set of functions which enable me to write; it serves no other purpose that I can see. This part takes charge when I am at a keyboard, or even outdoors, or in the middle of doing something that ostensibly has nothing to do with writing. Agnes sometimes tells me that I am a good writer, but a little man; and it is true that during long periods I have no human passion except on paper. I have always had this problem, and it cripples a real-life close relationship. I try to lead a normal life, and respond to people, but I am often miles away; all at once, whatever I am doing becomes mechanical, I answer questions absentmindedly, am only half aware of what I am supposed to be doing, stop paying attention to the other person or do not understand what he is saying; this is because, for no reason, some thought has struck me, which I start trying to integrate with characters, situation, surroundings, dialogue. Mentally, I am already writing it down, trying to memorise it before it can get away, and the fact that I am not physically doing so makes me frustrated, irritable and unreasonable, impatient of being approached or interrupted.There is only one image that I can offer to help explain this syndrome. My behaviour at such times reminds me of this computer I’m writing on now and its array of hidden files, files which hold the functions that make it the subtle and flexible machine it is—memory, comparison, exchange, replace, obliterate, restore. These files are written in symbolic language, and even if the viewer could understand them when they were shown to him, they never are shown, because the machine knows that it is not necessary to show them, except to an expert, who has his own access to the hidden files if for instance the machine breaks down. Like the computer’s, the writer’s performance is judged on the final, visible quality of his output rather than the obscure, cryptic processes that contributed to it.In love, though, the other, in order to know the whole person, needs access to all of him, including his hidden files; but the subject often cannot reveal them. This is unfortunately the case with me. Outwardly—and genuinely as far as it goes, which is all the way up to the hidden files—I appear to be the most accessible person you could meet. I think most of my friends would agree with that. The change that I undergo while I am writing disturbs the other; disappointment or anger replaces love as he discovers that the gap between appearance and reality is very wide—indeed I apparently become the complete reverse of what the other thought I was.I think a genuine human problem is that people are so used to living with themselves that they often fail to realise how bizarre they appear to others; anyway, I know that that is true of me. I am less egocentric than subject to an obsession; while the fit is on me everything and everyone else is allowed to slide—parked in a siding while the express roars through. While I’m writing I write absolutely: on the other hand, when I am not writing, I do absolutely no work at all—which in turn worries the other, and justifiably, as deeply as its opposite mood does. When the other realises that the clue to this mode of behaviour lies in the hidden files, he feels that his need for access to those files is all the greater. The relationship is in peril—he must inspect them. But in my case the hidden files cannot be inspected; I have not the means to reveal them.These memoirs are an attempt to break the codes and gain access to them, although even when open they will not have the readability of a novel; after all, the files only describe functions.The fact that I am this machine and not a different one, better oriented to the other, and that I am deceptive exactly because the hidden files are present although unseen, is a source of distress to me as well as those close to me. Yet none of us, apart from minor modifications, have any choice but to be what we are.