Finch: Finding a Way into the Novel

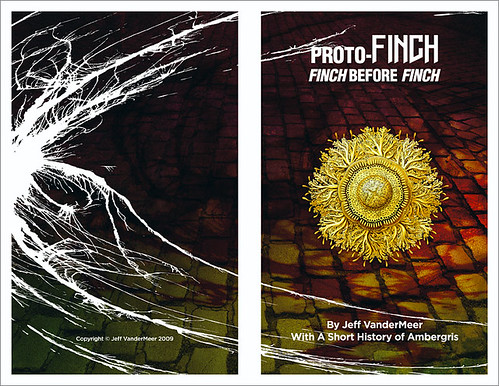

(Chapbook cover for Finch limited edition, available through Underland.)This is the fourth of a series of posts on my novel Finch. Finch is set in my fantastical city of Ambergris, but also borrows heavily from such genres as the spy novel, the noir mystery novel, and certain types of political thrillers. In the novel, an inhuman subterranean species called gray caps has risen up to take control of the city and subjugate the human population. As in Paris during Nazi control, the gray caps attempt to give a semblance of normality by providing institutions of order like a police force, even though these institutions are often merely a façade or horrible/absurd in nature. Against this backdrop, reluctant detective John Finch must solve a strange double murder.You can find the other entries here:Finch and Black Hawk Down: Repurposing TechniqueFinch's Opening--intro postFinch's Opening--discarded approachesYou can read the first 68 pages of Finch here.To recap, I felt I had four possible entry points to the novel:

(Chapbook cover for Finch limited edition, available through Underland.)This is the fourth of a series of posts on my novel Finch. Finch is set in my fantastical city of Ambergris, but also borrows heavily from such genres as the spy novel, the noir mystery novel, and certain types of political thrillers. In the novel, an inhuman subterranean species called gray caps has risen up to take control of the city and subjugate the human population. As in Paris during Nazi control, the gray caps attempt to give a semblance of normality by providing institutions of order like a police force, even though these institutions are often merely a façade or horrible/absurd in nature. Against this backdrop, reluctant detective John Finch must solve a strange double murder.You can find the other entries here:Finch and Black Hawk Down: Repurposing TechniqueFinch's Opening--intro postFinch's Opening--discarded approachesYou can read the first 68 pages of Finch here.To recap, I felt I had four possible entry points to the novel:

(1) John Finch, standing over two dead bodies, at the crime scene. Beside him are his inhuman gray cap boss, Heretic, and a Partial (a kind of traitor willingly working for the gray caps).(2) John Finch poised at the door to the apartment, inside of which are the bodies, the Partial, and Heretic.(3) John Finch at the police station, receiving the call from Heretic about the murders, telling him to come to the apartment.(4) John Finch in some guise giving readers an overview of the fantastical city of Ambergris in which the story takes place before being called to the crime scene.

I tried all four of these approaches, but finally settled on #2. Why? See below.***

(2) John Finch poised at the door to the apartment, inside of which are the bodies, the Partial, and Heretic.

Ultimately, because the focus of the novel is on John Finch, I decided on an opening with him at the door to the apartment, about to go inside. This is the moment of maximum tension for Finch. On the other side of the door, he’s about to encounter not just his inhuman boss, the gray cap Heretic, but also a Partial, a human traitor who has had one eye replaced with a gray cap spore camera. These things scare and stress him more than encountering bodies. Ambergris is a war-torn landscape in which dead bodies are a hazard of living there. A couple more, even dead under mysterious circumstances, aren’t going to phase John Finch—especially since he has a past serving in the Hoegbotton militia as a soldier. It’s also the first of the doors Finch will go through, and that initial moment of tension repeats throughout. Most times, Finch has a choice—not a great choice, but a choice nonetheless. He can go through the door, or he can turn back. Each time he braves a door, in a dangerous context, the reader learns something about his character. (And, in a context where he’s often a pawn, opening a door can be an act of defiance as well as an act of bravery.)Now, just as John Finch goes through doors—many doors—in the novel, on another level I was thinking of the doors the reader would have to open to enjoy the novel, in a sense the progressions. Sometimes a satisfactory entry point can be accomplished in part by the context provided by the description on the back cover of a book. Other times, the burden falls entirely on the opening chapters. Mary Doria Russell thought about this extensively when writing her science fiction novel The Sparrow. Her decision, to me, seems a little extreme, in that she decided to flense most descriptions in the first hundred pages that might have served to confuse readers not familiar with SF—which is to say, elements of the future. This gained her readers, but destabilized the novel to some extent.But I also didn’t want the reader to get the bends entering what I knew would already be a strange setting and situation. While the situation itself—a double murder—would in fact result in a stabilization of reader expectations because it’s so familiar from movies, TV, and detective novels, I still felt further “normalization†between the reader’s perspective going in and the world of the novel would be necessary.So starting off with Finch at the door gained me the space to introduce strange elements one by one while still beginning at the moment of maximum tension for the main character. The progressions are very simple but important:---Finch enters apartment---Finch encounters the Partial---Finch encounters Heretic---Finch encounters the dead bodies---Heretic leaves and Finch is dealing with dead bodies and the Partial---The Partial leaves and Finch encounters the city The physical space supports these progressions: hallway leading to doorway leading to living room/kitchen leading to balcony. (The physical space is also representative of transformation—from human to non-human, from Finch to Partial to Heretic. To pass through that space, something of the inhuman psychically rubs off on Finch. It’s also useful to put space between the Partial and Heretic as emblematic of things that occur later in the novel.)The point of these progressions, however, is not just to acclimate the reader to a surreal place, nor just to let the oddness of the Partial sink in before we get to the oddness of Heretic, and then the peculiarities of the case Finch must solve.No, it’s also to show Finch in different states of action and reaction. His reaction to the Partial is largely contemptuous, but we wouldn’t have gotten to see that so clearly if he’d encountered both the Partial and Heretic together, nor seen so sharply the contrast created by then having Heretic once more out of the room. Further, the Partial is fairly scary, so Finch’s reaction establishes some sense of his backbone—before then meeting Heretic, who obviously scares the crap out of Finch. Because Finch is scared of him, but not of the Partial, this potentially ups the tension because to most readers the Partial is fairly daunting. Thus, Heretic must be off the charts.We then also see Finch with the bodies—and we get a sense of who he is from the fact that although he is a reluctant detective, if he’s going to do a job, he’s going to try to do it thoroughly. He’s going to try to do it well—and this with the Partial snapping at him, after Heretic has left. This further establishes that John Finch is trying to do the right thing, even under extremely difficult conditions.

The physical space supports these progressions: hallway leading to doorway leading to living room/kitchen leading to balcony. (The physical space is also representative of transformation—from human to non-human, from Finch to Partial to Heretic. To pass through that space, something of the inhuman psychically rubs off on Finch. It’s also useful to put space between the Partial and Heretic as emblematic of things that occur later in the novel.)The point of these progressions, however, is not just to acclimate the reader to a surreal place, nor just to let the oddness of the Partial sink in before we get to the oddness of Heretic, and then the peculiarities of the case Finch must solve.No, it’s also to show Finch in different states of action and reaction. His reaction to the Partial is largely contemptuous, but we wouldn’t have gotten to see that so clearly if he’d encountered both the Partial and Heretic together, nor seen so sharply the contrast created by then having Heretic once more out of the room. Further, the Partial is fairly scary, so Finch’s reaction establishes some sense of his backbone—before then meeting Heretic, who obviously scares the crap out of Finch. Because Finch is scared of him, but not of the Partial, this potentially ups the tension because to most readers the Partial is fairly daunting. Thus, Heretic must be off the charts.We then also see Finch with the bodies—and we get a sense of who he is from the fact that although he is a reluctant detective, if he’s going to do a job, he’s going to try to do it thoroughly. He’s going to try to do it well—and this with the Partial snapping at him, after Heretic has left. This further establishes that John Finch is trying to do the right thing, even under extremely difficult conditions. (A version of the opening that shoved Finch, the Partial, Heretic, and the bodies all together in the same space, immediately. In a non-fantasy novel this approach might've been just fine. In Finch, it would've destabilized the novel by undermining effects that achieve full fruition in the latter stages of the story arc.)It’s important for the reader to see Finch interact with the Partial both before and after Heretic has left the building for a couple of reasons. First, Finch acting in the exact same way despite being rattled by Heretic demonstrates a certain amount of groundedness and level-headedness. He gets rattled, but he doesn’t stay rattled. Second, it’s useful for the rest of the novel to show the range and limits of the Partial’s general disdain for Finch. Third, the Partial is a recurring character but doesn't have many scenes--this is another opportunity to insert him into the narrative in a way that makes sense from a characterization point of view.These decisions may have stretched out the scene, but they're prefaced by an interrogation transcript that's a kind of prologue--Finch under great duress at an unspecified point in time. I felt that that element combined with the inherent questions raised by the two dead bodies offset the potential risk of the slowing the pacing slightly---while the rewards of the approach down the line were too great to ignore.Is a lot of this "business", like stage directions? Yes, and it's important to get that "business" right if you want to achieve more complex effects in a novel. I'm reading Skylark by Peter Straub right now and one thing I marvel at is the grace and art of his blocking. To some extent where characters position themselves and where they are in relation to other characters helps to define them as people. It also provides the anchor for a scene that, by allowing us to see clearly as readers, makes Straub so effective in things he's trying to accomplish on a chapter and story arc level. Similarly, in Finch I am trying to leverage simple building blocks into the foundation for something that will ultimately encompass elements of the thriller, the noir mystery, surreal fantasy/SF, the spy story, and several other forms of fiction...

(A version of the opening that shoved Finch, the Partial, Heretic, and the bodies all together in the same space, immediately. In a non-fantasy novel this approach might've been just fine. In Finch, it would've destabilized the novel by undermining effects that achieve full fruition in the latter stages of the story arc.)It’s important for the reader to see Finch interact with the Partial both before and after Heretic has left the building for a couple of reasons. First, Finch acting in the exact same way despite being rattled by Heretic demonstrates a certain amount of groundedness and level-headedness. He gets rattled, but he doesn’t stay rattled. Second, it’s useful for the rest of the novel to show the range and limits of the Partial’s general disdain for Finch. Third, the Partial is a recurring character but doesn't have many scenes--this is another opportunity to insert him into the narrative in a way that makes sense from a characterization point of view.These decisions may have stretched out the scene, but they're prefaced by an interrogation transcript that's a kind of prologue--Finch under great duress at an unspecified point in time. I felt that that element combined with the inherent questions raised by the two dead bodies offset the potential risk of the slowing the pacing slightly---while the rewards of the approach down the line were too great to ignore.Is a lot of this "business", like stage directions? Yes, and it's important to get that "business" right if you want to achieve more complex effects in a novel. I'm reading Skylark by Peter Straub right now and one thing I marvel at is the grace and art of his blocking. To some extent where characters position themselves and where they are in relation to other characters helps to define them as people. It also provides the anchor for a scene that, by allowing us to see clearly as readers, makes Straub so effective in things he's trying to accomplish on a chapter and story arc level. Similarly, in Finch I am trying to leverage simple building blocks into the foundation for something that will ultimately encompass elements of the thriller, the noir mystery, surreal fantasy/SF, the spy story, and several other forms of fiction... (Beginning of the section in which Finch is looking out over the city.)Then, at the end of chapter 2, Finch stares out over the city. By this time, he’s run the gauntlet of Partial, Heretic, the bodies. He’s in a different emotional space than when the scene started—he’s more stressed now, even as he’s slightly more relaxed because Heretic is gone. When he looks out over the city, it’s with a sense of sadness and loss that’s compounded by what he’s just gone through—having to contend with the Partial, having to interact with Heretic—and thus he imbues the landscape he sees with that essential quality of emotion. Now, too, with the reader having experienced a small slice of what Finch’s life is like, that landscape means something more than if it had been presented first.Landscape not invested with emotion or point of view is inert, lifeless.Now, why did I use present-tense for the scene where Finch stares out over the city? I’ll tackle that question, and the question of use of present-tense throughout the novel, in one of my next posts on the novel.(For bonus points: anyone translate the Latin phrase Finch finds on the man's body? Anyone know where I took the gray caps' favorite symbol from?)

(Beginning of the section in which Finch is looking out over the city.)Then, at the end of chapter 2, Finch stares out over the city. By this time, he’s run the gauntlet of Partial, Heretic, the bodies. He’s in a different emotional space than when the scene started—he’s more stressed now, even as he’s slightly more relaxed because Heretic is gone. When he looks out over the city, it’s with a sense of sadness and loss that’s compounded by what he’s just gone through—having to contend with the Partial, having to interact with Heretic—and thus he imbues the landscape he sees with that essential quality of emotion. Now, too, with the reader having experienced a small slice of what Finch’s life is like, that landscape means something more than if it had been presented first.Landscape not invested with emotion or point of view is inert, lifeless.Now, why did I use present-tense for the scene where Finch stares out over the city? I’ll tackle that question, and the question of use of present-tense throughout the novel, in one of my next posts on the novel.(For bonus points: anyone translate the Latin phrase Finch finds on the man's body? Anyone know where I took the gray caps' favorite symbol from?)